A recent website security audit uncovered a sophisticated WordPress infection that used a fake Google reCAPTCHA overlay to trick users into running malicious commands.

At first, the website owner believed it was a new spam-prevention feature, but visitors soon reported that the verification kept failing and the site had become unusable.

Further investigation revealed that the infection originated from a hidden plugin called “hseo” that was secretly installed in the WordPress plugin directory. The plugin disguised itself as a harmless SEO utility but actually served as a loader for a staged JavaScript payload delivered through the Binance Smart Chain (BSC) testnet. The malicious overlay and clipboard hijack were generated entirely from this plugin’s code.

Incident snapshot

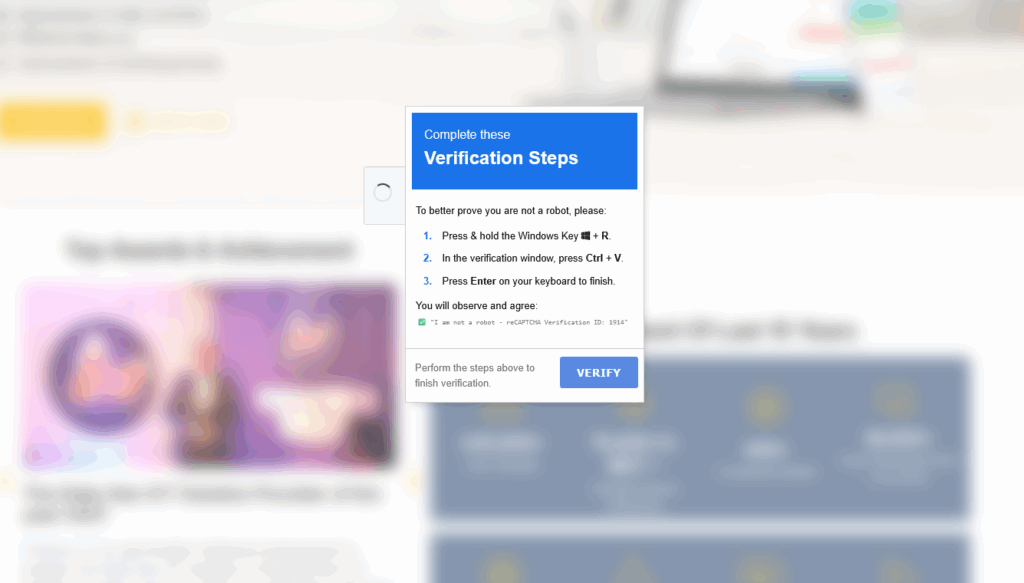

Visitors to the infected website saw a full-screen fake reCAPTCHA that closely copied Google’s official design. The overlay used the same logo, colors, and layout, completely blocking normal site navigation.

When users clicked the verification checkbox, the page copied a malicious command into the clipboard and displayed step-by-step instructions to run it in Windows. That instruction sequence explicitly guided users to open the Run dialog, paste the clipboard contents, and execute the command.

If followed, those steps would open a headless instance of Microsoft Edge and download a remote HTA file, allowing attackers to install additional malware such as information stealers or remote access tools.

How we detected it

1. Identifying the fake reCAPTCHA

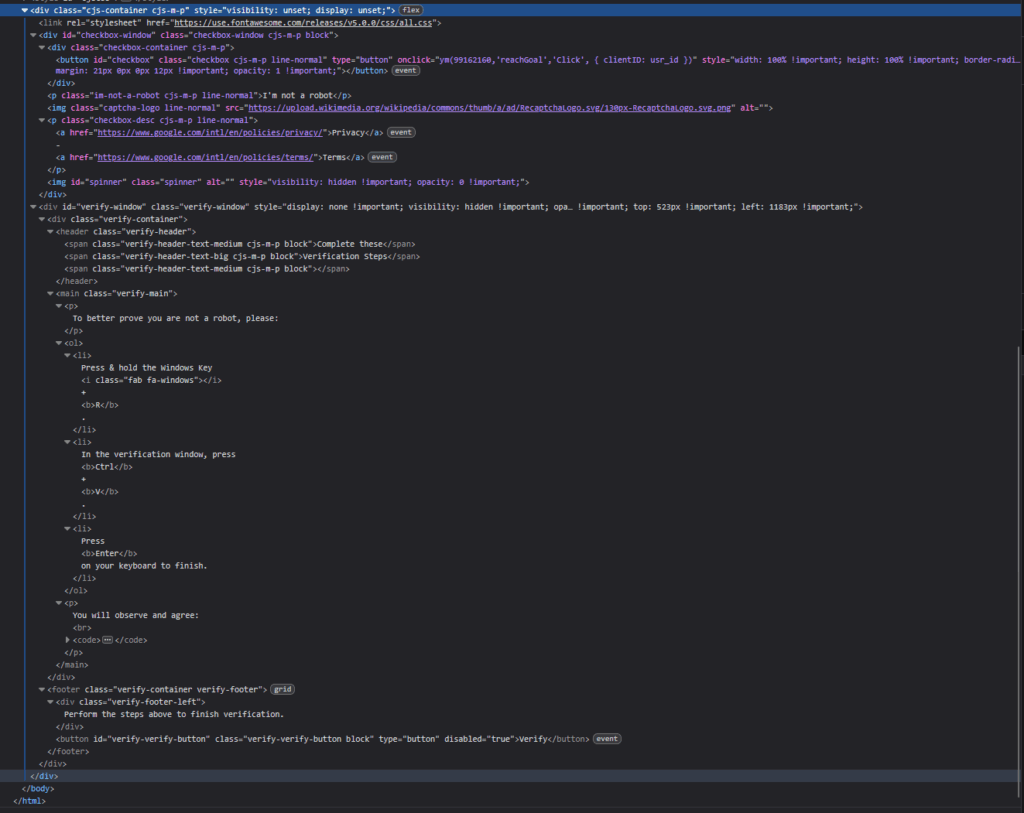

We began by reproducing the issue in a clean browser session. Inspecting the HTML immediately confirmed that the CAPTCHA elements were not loaded from Google’s official domains. The familiar layout and logo were copied, but the underlying source was fake.

2. Manual inspection revealed a hidden plugin

Automated security plugins and internal malware scanners were unable to detect the source of the infection. File integrity checks and database scans showed no anomalies.

A deeper manual inspection of the /wp-content/plugins/ directory uncovered an unfamiliar plugin folder named “hseo.”

This plugin did not appear in the WordPress dashboard or the installed plugin list, indicating it was intentionally hidden. The plugin’s code attempted to mimic a sitemap generator and SEO optimization tool to appear legitimate at first glance.

3. How the plugin worked

The decoded function made repeated JSON-RPC eth_call requests to the Binance Smart Chain Testnet. Browser network logs showed a sequence of POST requests to this endpoint. Each response contained a small JSON object with hexadecimal data in the result field. When converted from HEX to Base64 and decoded, the data produced another JavaScript stage that was executed dynamically using .

4. Clipboard hijack and payload analysis

In a controlled sandbox environment, clicking the fake verification checkbox triggered the Clipboard API, writing the following command automatically:

This command instructed Windows to open Microsoft Edge in headless mode, spawn cmd.exe, and download an .hta file from a malicious domain. Executing that file could compromise the system completely.

5. Verifying the source and persistence

Code review confirmed that the hseo plugin handled the full infection workflow:

- It hid itself from the plugins list by filtering the active plugin array.

- It generated a fake sitemap and robots.txt to appear legitimate.

- It executed blockchain API calls to fetch encoded payloads.

- It injected decoded JavaScript into the site header using wp_head.

- It included helper functions to regain administrator access and remotely evaluate PHP through hidden routes.

Because the malicious activity originated from a legitimate plugin file, not a database entry, internal scanners and file-based monitors failed to flag it.

7. Immediate containment and documentation

Once the malicious payload and injection point were confirmed, we immediately reset all admin credentials, invalidated sessions, and isolated the site for further cleanup. Network captures, decoded scripts, and clipboard payloads were preserved for forensic analysis and indicator documentation.

How the Infection Entered

1. Initial Foothold

The breach began with a critical vulnerability in one of our installed plugins, which exposed an authenticated-to-administrator privilege escalation pathway. The attacker exploited this flaw to gain complete administrative access. Our log analysis indicates the first successful admin session occurred within minutes of an external IP scanning the vulnerable plugin, a timeline consistent with a typical exploit-and-login attack pattern.

2. Weaponization of a Legitimate Plugin

Once the attacker secured administrator privileges, they installed “Insert Headers and Footers” (WPCode), a legitimate plugin that provides a graphical interface for site-wide script injection without requiring direct modifications to theme files. This approach was strategically chosen to circumvent file-integrity monitoring systems and ensure persistence even through theme or core WordPress updates.

3. Database-Resident Payload

Attackers gained access to the site using stolen or brute-forced administrator credentials. Once inside, they manually uploaded the hseo plugin into the plugin directory. Because it looked like a standard SEO tool, the installation left no immediate signs of intrusion.

4. Hidden behavior and payload delivery

The plugin’s code included both benign SEO functions and hidden malicious routines. On activation, it registered hooks to the wp_head action and silently injected a Base64-encoded JavaScript loader into every page.

This loader contacted the BSC testnet to fetch additional scripts, decode them, and render the fake CAPTCHA overlay on the client side.

Why Internal Scanners Missed It

Most WordPress malware scanners rely on database scanning or file signature comparison. In this case:

- The plugin’s code did not modify core or theme files.

- The injected script was generated dynamically in memory during page rendering.

- The blockchain delivery method prevented static detection because no fixed malicious domain or payload existed in the code.

This made the attack extremely difficult for traditional security tools to detect.

How external scanning helped

A remote behavioral scanner such as SecureWP Scanner, can detect this type of infection because it observes the site as visitors see it. Remote scanners analyze a website from the outside in, detecting malicious overlays, obfuscated scripts, and behavioral anomalies that file-based scanners might overlook.

Takeaways for WordPress security and malware defense

- Blockchain is becoming a new command channel. In this case, the malicious plugin used the Binance Smart Chain testnet to fetch encoded payloads. Public blockchains provide attackers with a resilient, decentralized infrastructure that cannot easily be taken down or blocked. Security teams should now treat blockchain RPC endpoints as potential malware sources and monitor outbound calls to them.

- Front-end malware is harder to spot. Modern infections use encoded JavaScript, blockchain hosting, and social engineering instead of simple PHP backdoors.

- Pair internal and external scanning. File and database scanners alone cannot detect browser-based payloads. Combine them with remote scanners that observe real page behavior.

- Harden access controls. Use strong, unique passwords, enable two-factor authentication, and review admin accounts regularly.

- Monitor unusual domains and blockchain calls. Outbound requests to RPC endpoints or encoded JavaScript in headers are key red flags.

- Apply a strict Content Security Policy (CSP). Limiting allowed script sources prevents inline and data-URI script execution without breaking legitimate functionality.

Final thoughts

This WordPress fake reCAPTCHA hack illustrates how attackers blend technical sophistication with social engineering to bypass detection. A single hidden plugin can load multi-stage malware through decentralized infrastructure while remaining invisible to normal administrators.

Combining proactive access security, behavioral scanning, and manual inspections is the best defense against this new class of hidden plugin malware attacks.